|

Louisville Scene Feature -

March 20, 1971 |

WKLO

Rock Radio: Sweet Sound of Money

Gone are the beeps and

the shouts, the treasure hunts and the blare, but the cash registers

jingle on.

By John Christensen

Louisville Times Staff Writer

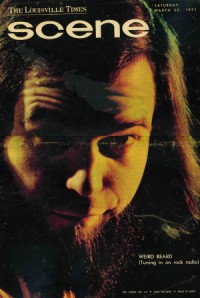

WAKY's Weird Beard

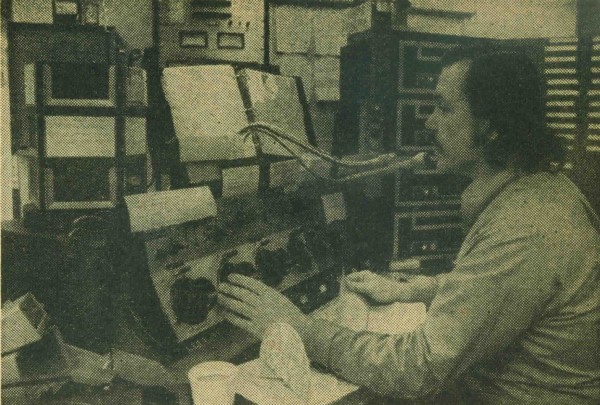

On the wall in Carl Truman

Wiglesworth's office at Radio WKLO, off from the posters of Creedence

Clearwater Revival, The Dells, Grand Funk Railroad, The Who and Bob

Dylan (upside down), over in a corner where it is mostly obscured by the

open door, is a picture.

It's a large, black-and-white glossy of Lee Gray, a WMCA (New York) Good

Guy! ("BONG!"), with a big, gleaming smile and an air of aggressive good

cheer that so much as says "Look out Levittown High, I'm coming your way

this Friday night with Ramar of the Jungle and the Rock Crock!"

Written on the left in black magic marker, in high reaching letters, is:

"If I told you how much I miss Louisville, it would take tears." And on

the other side of that New York show biz-personality smile, "Love you

all, Lee."

Lee Gray: Louisville's not Brylcreem, but

he came back. He is at WKLO.

Lee Gray had been at WKLO for five

years, spurned two previous offers to go to the big time and was well

satisfied until he got yet another offer. He accepted. Within months

after he left, he was back at WKLO where he is now the morning man,

doing the 6 to 10 a.m. shift playing the "Working Girl's Special" and

telling his listeners, "I hope this is the best day you've ever had."

Shortly before Gray returned, Bill Bailey, the self-proclaimed Duke of

Louisville as he was the Duke of Houston, Winston-Salem, Anchorage and

Salt Lake City before that, left to become the Duke of Chicago. Going to

the big time, Bailey was getting a reported $300,000, five-year contract

with a chance to make more at 50,000-watt, clear-channel WLS, if his

ratings were strong.

And not a year later, WAKY here ran ads in the papers and on billboards

saying "Bill Bailey Came Home!" He came home, all right, tired of what

he called the "teeny-bopper" music WLS played, and tired of what others

called the management's attempt to muzzle him.

And he came to WAKY, not WKLO where he had an extremely popular morning

show, saying, "I go where the money is. I don't do this for fun."

The money is definitely there. Bailey, it is commonly known in the

business, has a base salary of $28,000, receives a talent fee for doing

commercials and gets $1,000 for each point he leads his competitor in

the ratings. It is also commonly known that Bill Bailey's morning show

is No. 1 in the ratings.

Gray, a knowledgeable source says, is probably making a base salary of

between $20,000 and $25,000 plus other considerations. Which leaves him

with something more than a fine-tooth comb himself.

The point is this: While Louisville is hardly cosmopolitan and "big

time" only in the money its basketball team plays college seniors, it is

a lucrative marker for (sorry parents) rock radio.

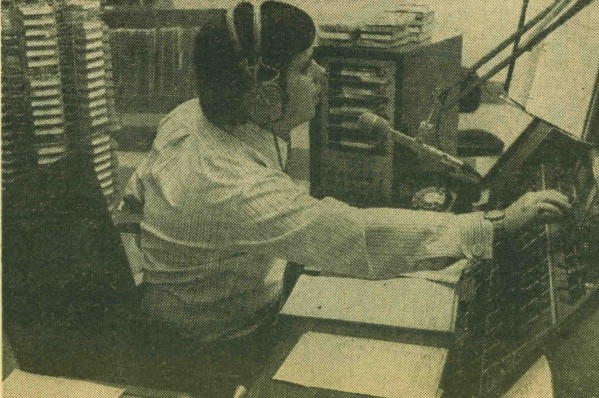

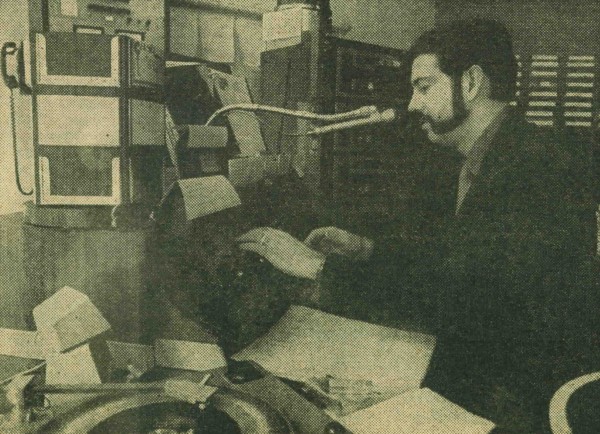

People in glass houses sell rock. "Dude"

Walker in WAKY's Fourth Street "showcase" studio.

IN THE BEGINNING…such a beginning!

A madman, everyone decided, had come to town. His name was Gordon

McLendon and he made such an outstandingly good offer for WGRC - an

exceedingly good price, agreed those in the know, for a station that was

sixth in the ratings - that its owner agreed to sell, although he hadn't

even thought of it.

Interestingly, McLendon began getting other offers. The Brooklyn Bridge?

How about a promising sand bar in the Ohio River?

But McLendon was undaunted, un-flapped and most important, uninhibited.

He inserted spots in the station's programming, promising that on July 7

of that year (1958), Louisville would go "wacky." What people didn't

know was that he meant "WAKY," since he planned to change the station's

call letters.

On the appointed day, he did just that, then ordered his disc jockeys -

imports from Top 40 (rock) stations in Texas and Louisiana - to play

"The Purple People Eater Meets the Witch Doctor." For two days straight.

After which, he promised a boggled reporter from The Courier-Journal

there would be a more "flamboyant" (i.e., rock 'n' roll) format

instituted.

It was.

And it was devastatingly simple (simple-minded, many would argue). The

disc jockeys arrested their listeners with a hard-sell, hard-rock,

rapid-fire delivery, very much like the guy who does those

1,000-words-a-minute commercials on late night TV for Veg-A-Matic and

other wondrous household items: "THAT WAS BOBBY DARIN AND 'SPLISH

SPLASH!' NUMBER THREE ON THE BIG 11 SURVEY! STICK AROUND! YOU'LL HEAR IT

AGAIN IN FOURTEEN MINUTES! BLANG-G-G-G!! WAKY, THE BIG 790, REACHING YOU

AND ONLY YOU WITH ALL THE HITS!! BLANG-G-G!!"

News was delivered in the same upbeat fashion; harsh, staccato blasts

from neo-Walter Winchells with a "BEEP!!" to punctuate each item. The

news itself was seldom more than a random collection of glorified

headlines, with a hyped treatment. Whether Elvis Presley's wife had a

baby or 31children were killed in a school bus crash, it was announced

with the same strident, detached voice anxious only to keep things

"BEEP" moving.

The noise was unremitting. The music was, to the adult's way of

thinking, a harsh, throbbing clash of sounds inconsistent with sanity,

beauty and peace. It was also exactly what the kids wanted, and that was

(and is) the target audience.

In fact, all of Louisville was fascinated, as if the station had been

overrun by a crazed band of unemployed carnival barkers who locked

themselves in and turned up the music. Most thought the frenzy would

pass, that the cacophony would shatter the nerves, and we'd all go back

to Perry Como.

Hah! McLendon came up grinning as WAKY exploded from sixth in the

ratings, with but 5 per cent of the listening audience, to first in the

ratings, with more than 40 per cent of the listeners. And did it in one

month.

Suddenly, people who had thought McLendon to be not a little soft in the

head were trying mightily to put money in his pocket. Advertising. And

WKLO, basically a country music station begun in 1948, switched to a Top

40 format in August 1959, duplicating McLendon's successful formula.

In 1962, McLendon sold his still successful, still No. 1,

first-in-Louisville rock station to the LIN Broadcasting Corp. for $1.35

million. A healthy profit and proper reward for someone with 20/20

foresight.

IN CASE YOU didn't know, rock radio continues to flourish. There are 12

AM stations in the metropolitan area (including WSAC in Ft. Know), and

all of them are making money. Some more than others, but making money

nonetheless.

Jeff Douglas of WHAS: And a Ya Ha

to you, too.

"There are three stations in the area

with a gross billing of more than $1 million a year," said WAKY station

manager Don Meyers. "And we're one of them." The other two, it seems

safe to say, would be WAVE and WHAS. WKLO, also doing quite well, is not

far from the million mark.

Stations make money, because their product - rock music, country music,

middle-of-the-road stuff, you name it - costs them nothing. Their

expenditures are limited to salaries, utility bills, etc. Meyers added,

neither boasting nor moaning, that "I think it's safe to say we also

have the highest payroll in the area."

Which doesn't really bother him since WAKY also occupies the top spot in

the ratings. (A note here about ratings. There are nearly as many

ratings as stations, and they are based on everything from the sex of

the listener to the number of pairs of white shoes he has. Each station

is fond of quoting the rating which lists it highest - for obvious

reasons. The hapless reporter, then, is left to wander through the

labyrinth and make a coherent road map. Therefore - a flourish of

trumpets, please - we're going with WAKY.

Something else. While rock radio has refused to fold, as was, and is,

fervently hoped for by the more staid citizens in our republic, it has

refused even to hold its ground. Rather, it is advancing, expanding,

acquiring new listeners the way Israel enlarged its holding in the

six-day war of 1967. Where it once claimed listeners hovering around the

age of puberty, it now reaches more people up to the age of 34 than any

other kind of radio. Or that's what they say.

Their argument is persuasive. The kids who loved "Blue Suede Shows" and

"Hound Dog" have stayed with the music, and it has been 15 years and

then some, and many of them are mothers and fathers now. Meanwhile, the

bottom (in age) end of the market remains constant in its interest;

children go from guns and dolls to James Taylor and The Jackson Five -

and guys and dolls.

Another reason is the music itself, says Johnny Randolph, the

27-year-old program director at WAKY. Seated in his comfortable, paneled

office, he gestured at a speaker in his office from which came The Fifth

Dimension, singing "Love's Lines, Angles and Rhymes." The music," he

said, "is more palatable now. Like this one.

"Besides that, the accent in our society is young. Look young, stay

young - and people are discovering that rock stations are not as bad as

they thought. And during all this, the middle-of-the-road stations like

WAVE and WHAS were asleep. Now, they're coming back and they play much

of the same kind of music we're playing."

The reason is simple. "From a standpoint of revenue, there's bundles of

money in teen-agers and young adults," said Randolph.

In the past year and a half, WHAS, Radio 84, the clear-channel,

50,000-watt middle of the roader with a daytime listening audience in

five states, has vastly changed its programming. And it is a change

directly attributed to rock.

It hired a new program

director, Hugh Barr, a 35-year-old veteran of several rock stations,

most recently in Salt Lake City, and to him must go the credit, or

discredit if you will, for the transformation.

"We've always been strong with the people over 50," he said recently,

"But we like to broaden our appeal. For two decades, we had been playing

what we call 'chicken rock.' I mean by that, we'd play Ray Conniff

instead of the original version. And people have either gotten into the

habit of listening to us, or not, because of that. Their habits are

ingrained.

"Now, we're tying to think in terms of today's music. We've tried to

take a whole block of what's best in today's music wherever it comes

from - some country, some soul, some hard rock, some pretty ballads.

Like the album 'Jesus Christ Superstar.' That's really big with the

kids. They go around singing songs from it in my kids' school. But

nobody plays it. So we play three or four cuts from it."

The rock station have tempered their formats, made them less offensive,

dropped the "BEEP" in their newscasts, eliminated the old

tear-up-the-city treasure hunts and are playing music that is a product

of the socially aware Sixties. That is, it's more thoughtful, better

written and orchestrated and more listenable to more people (and we can

thank The Beatles for much of it). But it is a commodity, nonetheless.

What then is there to choose from?

Personalities. If you don't like Bailey's rasping, cab-driver delivery,

you can cut over to the gentle voice and soothing ways of Lee Gary. If

you like neither manner, WHAS' Wayne Perky offers a happy voice each

morning - on the station that's making it a point of wishing you a happy

day.

In the afternoon "drive time" shows WKLO has Jim Rivers, a solid,

dependable pro; WAKY offers Gary Burbank, perhaps the cleverest man on

radio here and WHAS' Jeff Douglas boasts a low-key, but antic, wit.

Randolph says there are no particular instructions to his jocks, beyond

the simple axiom that they must say it quickly and be offensive to no

one.

Wiglesworth, Randolph's counterpart at WKLO, and Gray are spearheading a

particular approach at WKLO which, they think, is worthwhile. Each

Wednesday, they meet with the other jocks at the station and talk to

them about really listening to, and understanding, the things the

records say.

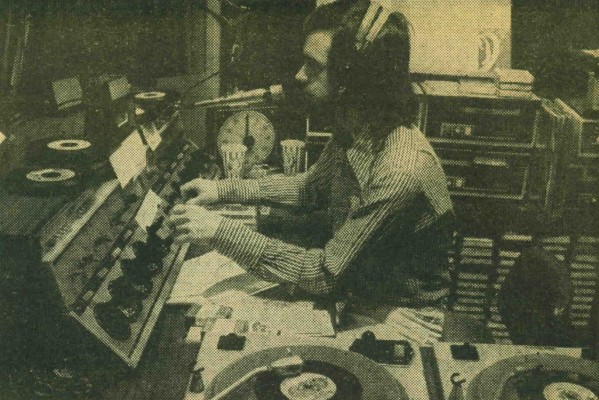

Carl Truman Wiglesworth: A little

relevancy music, please. Also at WKLO.

"The question is," said

Wiglesworth, "are we here to play games, shout 'Number 16!' and shuck

the folks or are we here to say something and give them something of

value? Like the record 'Doesn't Somebody Want To Be Wanted?' by the

Partridge Family. People over 65, people who are lonely, they understand

what they're saying in that song. But people 35 to 50 think there must

be something more to it - something hidden in the lyrics.

"The value of a jock is to understand the music enough and care enough

to say something about it besides 'Boy, this is really groovy!'"

The trend, at any rate, has been away from the programmed "zanies" to

"responsible" individualism. Responsible because no one is going to say

much of anything that would offend a large group of people, excepting

the heralded Skinny Bobby Harper who left WAKY not long after he baited

University of Kentucky football fans. He probably did his health a great

service.

It is individualistic in that the jocks (or "announcers,"

"personalities," whatever you will) are allowed, if not encouraged, to

develop personal styles, to be human, to be the guy who's communicating

with you, not talking at you. As Bailey says, "I actually communicate

with the average man. I'm not so much interested in entertaining them as

talking to them."

The money is indisputably good - the average salary for a jock in

Louisville is probably somewhere in the mid-teens. But is that

satisfaction enough? Why do men get into the business?

Weird Beard, whose real

name is Carl Markert, is a small, pale man, just turned 26, who decided

early what he wanted. "I was sick in bed for two years as a kid and I

listened to radio all the time. I decided then it was a good way to make

a living.

"I think all jocks would like to think that throngs of people flock to

the radio to turn on their show, but I don't think it exists anymore. If

I'm sick, there's only a handful of people who'd turn it off because the

Beard wasn't there, 'cause whoever replaces me plays the same stuff.

It's the music the people want."

He paused for a moment. He has a late night show, and the street was

empty. Then a car went by, slowly, and a girl waved to him. "I like to

play records, being the Weird Beard, being a part of so many people. I

like meeting the artists who come into town. I like who I've made myself

become."

Weird Beard at WAKY: Put a star on the

door.

IT STARTED here with

Gordon McLendon, a noisy, boisterous industry not unlike a squally baby.

Now, it's in the hands of men like Wiglesworth and Randolph, more

sedate, by comparison, but still quick-paced and loud. The lesson

learned after 13 years, and advanced by a man, Barr, whose station has

learned only too well from rock radio, is this: "If you're doing the

same thing a year from now that you're doing today, you're in trouble."